The South American seismic belt, a region of intense geological activity, stretches along the western edge of the continent, marking the boundary where the Nazca Plate plunges beneath the South American Plate. This subduction zone is responsible for some of the most powerful earthquakes and volcanic eruptions in recorded history. The Andes Mountains, which run parallel to the coast, are a visible testament to the colossal forces at work beneath the Earth's surface. The region's seismic activity has shaped not only the landscape but also the lives of millions of people who call this volatile area home.

Earthquakes in this belt are frequent and often devastating. The 1960 Valdivia earthquake, with a magnitude of 9.5, remains the strongest ever recorded. It triggered tsunamis that reached as far as Hawaii and Japan, demonstrating the far-reaching consequences of seismic events in this region. More recently, the 2010 Maule earthquake off the coast of Chile, measuring 8.8 in magnitude, caused widespread damage and highlighted the ongoing vulnerability of communities in this seismically active zone. These events serve as stark reminders of the immense power lurking beneath the Earth's crust.

Volcanic activity is another defining characteristic of the South American seismic belt. The Andes host numerous active volcanoes, including Cotopaxi in Ecuador and Villarrica in Chile. These volcanoes pose significant risks to nearby populations, with the potential for deadly eruptions, lahars (volcanic mudflows), and ash clouds that can disrupt air travel across continents. The 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia, which melted glaciers and sent deadly lahars through the town of Armero, killing over 23,000 people, stands as one of the worst volcanic disasters in modern history.

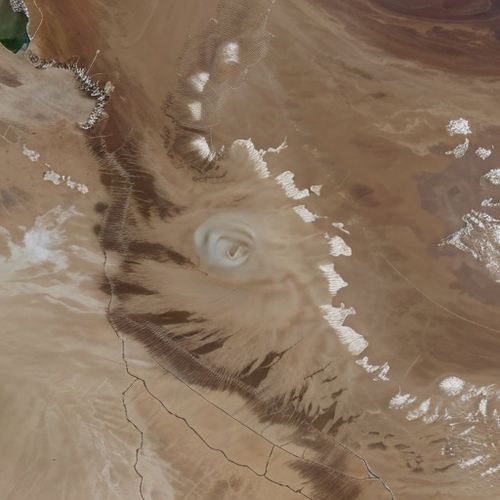

The geological processes shaping this region occur over immense timescales but have immediate and dramatic impacts. The Nazca Plate's relentless march eastward at about 7-8 centimeters per year creates constant stress along the plate boundary. When this stress is released suddenly, it generates earthquakes that can shake the ground for hundreds of kilometers. The subduction process also generates magma that feeds the Andean volcanoes, creating a dual threat of both seismic and volcanic activity that makes this one of the most geologically hazardous regions on Earth.

Scientists monitor the South American seismic belt closely, using networks of seismometers, GPS stations, and other instruments to track ground movements and volcanic activity. This monitoring has improved significantly in recent decades, allowing for better earthquake early warning systems and volcanic eruption forecasts. However, predicting exactly when and where the next major event will occur remains challenging. The complex interactions between tectonic plates, the buildup and release of stress, and the behavior of magma beneath volcanoes all contribute to this uncertainty.

The human cost of living in this active seismic zone is significant. Major cities like Lima, Quito, and Santiago sit in the shadow of potential disaster, with millions of residents at risk. Building codes in these areas have become increasingly strict, requiring structures to withstand strong shaking, but older buildings and informal settlements remain vulnerable. Earthquake preparedness drills and public education campaigns aim to reduce casualties when the next major quake strikes, but poverty and rapid urbanization continue to exacerbate the risks in many areas.

Climate change may be adding another layer of complexity to the region's seismic hazards. Some researchers suggest that melting glaciers in the Andes could affect the stress distribution along faults, potentially influencing earthquake activity. Additionally, changing precipitation patterns might alter the likelihood of volcanic lahars during eruptions. These potential climate-seismic interactions are an active area of research, highlighting how Earth's systems are interconnected in ways we are only beginning to understand.

The economic impacts of seismic events in this region ripple far beyond the immediate disaster zones. Chile, Peru, and Ecuador all rely heavily on mining industries located in the Andes, and disruptions to these operations can affect global markets for copper, silver, and other minerals. Agricultural areas in the Andean foothills are also vulnerable to earthquake and volcanic damage, with potential consequences for food security. The tourism industry, drawn to the region's stunning landscapes and cultural sites, faces periodic disruptions following major seismic events.

Despite the risks, the South American seismic belt continues to fascinate scientists. The region serves as a natural laboratory for studying subduction zone processes, earthquake mechanics, and volcanic systems. Insights gained here contribute to our understanding of similar zones around the world, from the Pacific Northwest of North America to Indonesia's volcanic islands. Each major seismic event, while tragic, provides new data that helps improve our ability to anticipate and mitigate future disasters.

Looking to the future, the challenge for South American nations is to balance development with resilience. As populations grow and cities expand in this seismically active region, the potential for catastrophe increases. Investments in early warning systems, disaster-resistant infrastructure, and emergency preparedness will be crucial for reducing the human and economic toll of inevitable future earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The lessons learned in this region may prove valuable for other parts of the world facing similar geological hazards.

The South American seismic belt reminds us of the dynamic nature of our planet. The same forces that create breathtaking mountain landscapes and fertile volcanic soils also pose deadly threats to human settlements. Understanding and respecting these natural processes is essential for the millions who live in this geologically active region. As scientific knowledge improves and mitigation strategies advance, there is hope that future generations will be better protected from the Earth's powerful subterranean movements.

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 14, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 14, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 14, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 14, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 14, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Apr 14, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 14, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 14, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 14, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 14, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 14, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 14, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 14, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 14, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 14, 2025

By Olivia Reed/Apr 14, 2025

By William Miller/Apr 14, 2025